The impeccable command practiced by the watchmakers is perpetuated on the situation and dial thanks to Patek Philippe’s Rare Handcrafts department. Ever since its foundation in 1839, the company employed local artisans to decorate its own watches. An unadorned pocket watch was starting with elaborate engraving and guilloché, and moving on to the Genevan speciality of miniatureportrait painting in teeth, Patek Philippe watches became known throughout Europe for their exquisite artistry. With the dawn of industrialisation, a number of these artistic crafts dropped from favour and almost died out. The Stern family realised the danger that this posed and, regardless of a lack of demand for rare enamelled bits, maintained a retinue of musicians on board to safeguard their ancient professions. Each year, about 40 one-of-a-kind bits are made, including the wonderful domed table clocks that provide a perfect canvas for cloisonné enamelling. The arts of marquetry, gem-setting, guilloché, chainsmithing, enamelling – closionné, champlevé, paillonné and mini enamel painting – and – engraving are revered and supported at Patek Philippe. Watching Thierry Stern, the present president, enthuse about his master craftsmen has a bit of the Medici patron lauding Michelangelo’s most up-to-date work.

Patek Philippe’s American chapter is one of the very colourful in its own long history, with a celebrity player who was recently resuscitated at the selling of the most expensive pocket watch on Earth, selling for $24 million last November. Called the Graves Supercomplication, this amazing mechanical masterpiece with 24 complications was born, quite literally, out of jealousy. American automobile magnate James Ward Packard was blessed with a prodigious mechanical mind and became fascinated with Patek Philippe’s complex machines. He began his view collection in 1905 but his ultimate fantasy was to possess a grand complication – a watch with over three complications – and in 1927 received his Patek Philippe astronomical pocket view. Decked out with a brightly rotating celestial chart representing the night skies of his hometown Warren, Ohio, it also featured a minute repeater, a perpetual calendar with Moon phases, sunrise and sunset signs, along with an equation of time. Meanwhile, the Wall Street tycoon Henry Graves Jr., who was a regular client at Tiffany & Co. and an avid Patek Philippe collector, got wind of Packard’s grand complication and was damned if he wasn’t going to get one too. The brief to Patek Philippe was simple. Graves wanted the “most complicated watch on Earth” and, in 1933, was introduced with a pocket watch which fit the bill to perfection. Known as the Graves Supercomplication, the two-faced watch was endowed with a staggering 24 complications and, like his rival, a celestial chart of the night skies over New York.

Some time ago I received an email from a gentleman explaining his family had a Patek Philippe that once belonged to his grandfather, which they might want to sell. Eventually I got in touch with the gentleman’s 80-year old mother, Mrs M. The stereotypical story of a little old lady with valuable heirloom – well, this was it, and then some.

The watch turned out to be a Patek Philippe Calatrava ref. 530 in 14k yellow gold. A rare model, particularly in 14k gold, and desirable because of its largish 36.5mm case, the watch also had a black dial that was confirmed by the archive extract, making it one of just a few known. Prime examples have sold in the past for over US$100,000, with one topping US$300,000.

During my email correspondence with Mrs M, I made the offhand remark that the watch showed some wear, rendering it quite a bit less valuable than a pristine example. She replied that was indeed true, but the condition was a result of the watch having, in essence, survived the Holocaust. That left me feeling guilty for critiquing the condition.

Mrs M’s father had handed the watch to her mother moments before he was taken away by the Gestapo and sent to Auschwitz. Her mother never saw him again, but wore the watch every day for the rest of her life.

The ref. 530 as captured by Mrs M

The sheer magnitude of that left a vast impression on me. All vintage watches possess some sort of memory, invisibly etched into the metal, but few can convey the incredible tale of love, loss, and hope that this wristwatch does.

While there exist more valuable watches with more glamorous backstories, this Patek Philippe ref. 530 has a history and provenance worth recounting in detail. While the tale is unhappy, it is ultimately uplifting, ending as a story of survival and hope.

It begins in fin de siècle Budapest, then one of the two capitals of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (the other being Vienna), the cosmopolitan agglomeration of states that occupied a swathe of central Europe. The era was an elegant and alluring age, a brief period in the 20th century before everything came to an end when, as Sir Edward Grey put it in 1914, “The lamps are going out all over Europe, we shall not see them lit again in our life-time.”

Mrs M’s father was Jeno Gertler, born in 1903 to a prosperous Jewish Hungarian family that produced many prominent members in the arts and commerce. A cousin, Andre Gertler, was a renowned classical violinist (with his own Wikipedia entry), while another cousin, Viktor, was a noted film director (and is also on Wikipedia).

Though he was born in a small town, Jeno moved to Budapest to study law. He became a successful attorney, while also going into the motion picture business with his cousin Viktor. The duo distributed foreign and Hungarian films, both locally and in other European countries. And Jeno also owned three movie theatres in Budapest, named Alpha, Astoria and Universal, a reminder that once upon a time going to see a film was a glamorous enough activity that every cinema deserved its own name.

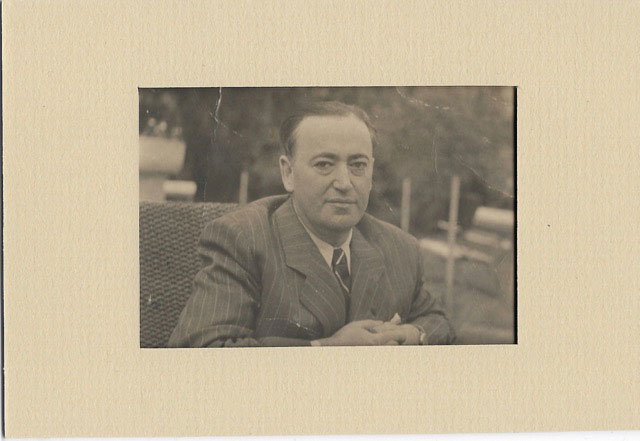

Jeno Gertler in 1943 or early 1944, with the Calatrava on his wrist

Jeno, in short, was an affluent and cultivated man – Mrs M describes her father as a “social man of refined taste” – the very sort who would buy a Patek Philippe wristwatch. And so he did, in 1941.

But Jeno did not buy just any Patek Philippe, but instead an oversized wristwatch with a black dial, the polar opposite of the 30mm, silver dial Calatravas that were most common at the time. He did have good taste.

Budapest in 1915, as the Gertlers would have known it. [Image Wikipedia]

A decade before he bought the Patek, Jeno had married Mrs M’s mother, Klara Fischer. Like Jeno, Klara hailed from a well-off family, with her grandfather having founded a cosmetics manufacturer, Compexa, as well as owning several pharmacies as well as a large mansion in the city.

The pair had met while playing tennis – both were ardent tennis players who won several prizes – living a warm and wonderful life in pre-war Budapest. A favourite haunt was the New York Kávéház, or New York Cafe, an swanky coffeehouse in Budapest that Mrs M describes as a “sophisticated meeting place of professionals, intellectuals, poets, writers and artists”. Mrs M adds that the cafe has since been restored to its original glory, leaving it looking much like it would have been when her parents and their friends socialised there.

The Gertlers had two children, Mrs M and her brother, and together the family led their lives in an upscale neighbourhood – residing in an apartment at Gróf Teleki Pal Utica 21, an address named after a Hungarian noble (Grof translates as “Count”) that was given a more appropriately Communist name after the war. Mrs M recounts an early life with vacations to lakes and mountains, along with days of piano and ballet lessons, while being attended to by nannies and doted on by grandparents.

Jeno and Klara Gertler (centre), celebrating New Year’s Eve in 1941 at the New York Cafe in Budapest. To the far right is Jeno’s cousin, Viktor.

Life became difficult during the Second World War, with Hungary entering on the side of the Axis Powers, but remained tolerable. That changed in 1944, when the Hungarian government started secret negotiations with the Allies, hoping to switch sides. In response, German troops marched into Hungary and toppled the government, replacing it with a pro-Nazi Fascist regime that began rounding up Jews and confiscating their assets. The Gertler’s homes and theatres were taken.

In late 1944, Jeno was detained by the Gestapo. Just before he was taken away, Jeno gave Klara his Patek Philippe for safekeeping, perhaps hoping he might one day retrieve it.

Hours after her husband’s arrest, realising the gravity of the situation, Klara took her two young children – Mrs M was just seven then – along with a handful of possessions, the Patek Philippe amongst them, and fled.

The trio were helped and hidden by friends and Catholics nuns along the way, and managed to survive the war. In 1947, with Hungary under Communist rule, Klara and her children boarded a train, ostensibly headed to the Budapest countryside. Instead they were destined for Paris – the plan was to obtain and visa to South America, where an uncle would provide them safe harbour. There was nothing left for them in Budapest.

The plan almost came undone at the border, which was manned by Russian troops who stopped Klara and the children, ordering they turn back. Klara pled and cried and pled again, and the soldiers relented. The family made it, and eventually moved to the United States.

Jeno never returned from Auschwitz, but Klara had his watch on her wrist every day for the rest of her life. She passed away in 1976 in Washington DC.

Mrs M has owned the Patek Philippe steadfastly since then, but it is now time for the watch to pass on. “The Patek Phillippe timepiece my father owned, which I have kept for almost 70 years,” writes Mrs M, “At age 80 I am finally finding myself able to let it go on its next journey and to get the attention it deserves.”

Mrs M has consigned the Patek Philippe to Christie’s, which will offer the watch in its upcoming New York watch auction that takes place on December 7 at 20 Rockefeller Center. The watch is lot 40 and estimated at US$100,000 to US$200,000, and you can see it online here.

The Calatrava, along with the other lots in the catalogue, can be seen in person during the preview exhibition that’s open daily from December 3 to 6.